|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Book Twenty-Four

|

|

|

|

The funeral games concluded, the men disperse to eat their evening meal and bed down for the night. But Achilles (a-KIL-eez) cannot sleep, such is his grief for Patroclus (pa-TRAH-klus). He tosses and turns and gets up and paces the shore. Dawn finds him yoking his chariot horses in order to drag Hector around the burial mound. All the gods look down from Olympus and pity Hector and want to send Hermes (HUR-meez) to spirit his body away. All the gods, that is, but Poseidon (puh-SY-dun), Hera (HEER-uh), and Athena (a-THEE-nuh). The two goddesses will never forgive the Trojans for the way their prince Paris had judged Aphrodite (a-fro-DY-tee) to be more beautiful than themselves.

|

|

|

|

Zeus (zyoos) says that in any case Hermes would never be able to snatch Hector's body without Achilles knowing it, since the goddess Thetis (THEH-tis) is always watching out for her son Achilles. But Zeus now decrees that Achilles must surrender the body if Trojan king Priam (PRY-am) pays a ransom, and he sends his messenger Iris to fetch Thetis so that she might be informed of this decree. Iris finds the sea-goddess in her underwater cave and brings her to Olympus, where she sits in honor beside Zeus in Athena's place. The supreme god instructs her to tell her son that if he fears the wrath of Zeus he must give Hector back in return for a ransom, which Iris is now dispatched to arrange.

|

|

|

|

Thetis conveys the message to her son, who submits to Zeus's decree. Priam is informed of the ransom plan by Iris and told that he must go to the Greek camp alone but may take one herald with him to drive the cart that will carry Hector back to Troy. The king immediately descends to his vaulted treasure chamber, high-roofed and fragrant with cedar wood. He tells his wife Hecuba (HEH-kew-ba) of the message from the gods and asks her opinion of the plan. "Where is the wisdom that you are famous for," she asks, "that you would go alone into the camp of our enemies?" Priam responds that he is willing to be killed by Achilles if only he can hold his son first.

|

|

|

|

From his treasure chests Priam takes dozens of fine woven garments, bars of gold, tripods, cauldrons, and a priceless goblet. He orders his nine remaining sons to load this onto a cart. Hecuba rushes up with a cup of wine to be poured on the ground with a prayer to Zeus for a favorable sign, which comes in the form of an eagle flying on the right-hand side. Priam mounts his chariot, and with the herald following in the cart, they set out across the Trojan plain. Zeus sends Hermes to shield them from the eyes of their enemies until they reach Achilles.

|

|

|

|

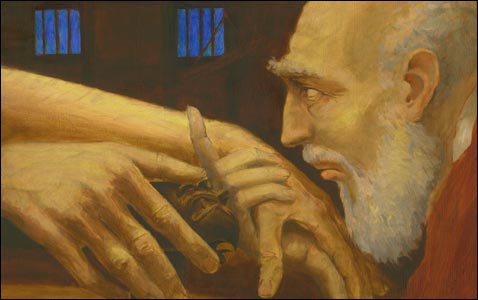

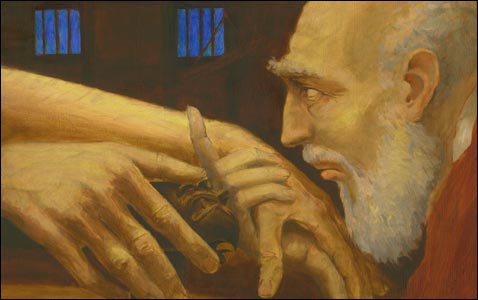

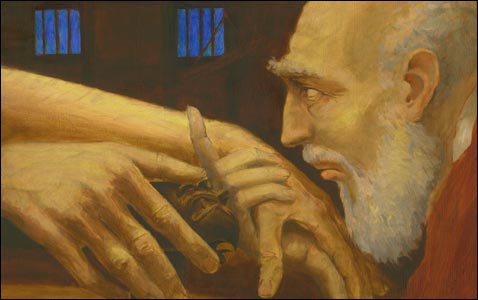

Adopting mortal form, Hermes takes the reins of Priam's chariot and drives through the gates of the Greek camp, having first put the sentries to sleep. Finding the wooden lodge that Achilles' men have built for him, the god reveals himself to Priam and takes his leave. Achilles and his captains have just finished dinner when Priam enters. Disregarding the others he makes straight for Achilles, clasps his knees, and kisses the hands of the man who has killed his son. He entreats Achilles to think of his own father, an old man like himself with no one to protect him, who at least still nourishes a hope that his son will return from Troy.

|

|

|

|

Achilles gently releases Priam's grasp. They both begin to weep, the one for Hector, the other for his own father and for Patroclus. When Achilles has had his fill of weeping, he invites Priam to sit down and stifle his sorrow, since there is nothing to be gained from lamentation. But Priam replies that he can't sit down until Achilles accepts the ransom and gives back Hector. This angers Achilles, to be prompted to do what has been ordained by the gods, but he and his lieutenants fetch the ransom from the cart, setting aside two robes and a tunic to cover Hector's body. He orders that the body be washed and anointed with oil and be kept hidden from Priam until this is done, lest he become angry at the sight of the desecrated corpse and provoke Achilles to a murderous rage.

|

|

|

|

It is Achilles himself who lifts Hector's body and places it on the cart, calling aloud to Patroclus not to be angry if he hears about the ransom down in the house of Hades (HAY-deez). Assuring Priam that Hector's body has been prepared for the homeward journey, Achilles asks how many days Priam wishes to allow for the funeral, so that he can hold back the Greeks from attacking during this time. Priam responds that if Achilles is willing, he would like nine days for mourning, a tenth for the funeral and funeral feast, and an eleventh day to heap up a burial mound. "On the twelfth day we will do battle, if we must," says Priam. Achilles responds that it will be so.

|

|

|

|

On a bed laid out for him, the old king soon falls asleep. But in the night Hermes comes to him and warns that if the Greek leader Agamemnon (a-guh-MEM-non) hears of his presence and his ransoming of Hector, an even greater ransom will be demanded for his own release. Hermes readies the chariot and cart and guides Priam and his herald out of the Greek camp and across the plain toward Troy. The god leaves them just outside the city, where throngs of grieving Trojans come out to meet them.

|

|

|

|

Hector is carried inside the city and laid on his bed, surrounded by minstrels leading off a song of lamentation, while the Trojan women wail in response. Among them is Hector's wife Andromache (an-DROM-uh-kee), who bemoans her fate and that of her orphaned son. Priam's queen Hecuba cries aloud for Hector, the dearest of her children. Helen, whose abduction had brought the calamity of war on Troy, recalls Hector as always having had a kind word for her, while now everyone recoils from her in loathing.

|

|

|

|

Priam instructs his people to go out and gather timber for the funeral pyre, without fear of ambush by the Greeks because of the word of Achilles. This they do for nine full days, then they lay Hector's body atop the pyre and set fire to it. The following morning they quench the embers with wine, gather the white bones of Hector, and put them in a golden urn. With tears streaming down their cheeks, they cover the urn in purple robes and bury it in the earth, with lookouts posted all around to guard against Greek attack.

|

|

|

|

Such were the funeral rites for Hector.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|