|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Book Two

|

|

|

|

That night Zeus (zyoos) sends a dream to Agamemnon (a-guh-MEM-non). Taking the form of Nestor, the dream urges Agamemnon to rouse his men for a great assault and promises in the name of Zeus that Troy is theirs for the taking. Awakening, Agamemnon confers in private council with his captains. He tells Nestor, Odysseus (oh-DISS-yoos), and the others of his dream and proposes to test the army by announcing his intention to abandon the siege. The army is mustered and Agamemnon makes a despairing speech: Nine years of warfare have brought him nothing but frustration; Troy will never be taken; they had better give up and head for home.

|

|

|

|

The entire army roars its assent and immediately sets about dragging the ships down to the sea. Hera (HEER-uh) sends Athena (a-THEE-nuh) to intervene. She in turn inspires Odysseus, who borrows Agamemnon's royal scepter and uses its authority and his own persuasive words on every captain he can find, urging them to constrain their men. The men themselves he berates and flogs with the scepter.

|

|

|

|

One soldier in particular, a hunchback named Thersites (thur-SY-teez), has been trying to amuse the troops with sarcastic comments about Agamemnon's lust for booty. Odysseus hits him so hard with the scepter that it brings tears to his eyes. The men find this so humorous that their morale begins to turn around.

|

|

|

|

Odysseus now makes a long speech in which he sympathizes with their sufferings and deprivation. A sailor at sea for a month grows homesick for wife and family, but this army has been in the field for nine years. He can't blame them for wanting to go home. But they must remember the prophecy of Calchas (KAL-kus) when the fleet was assembling at Aulis (AW-lis). A red-striped snake had crawled out from beneath the sacrificial altar and climbed up onto the branch of a tree where it devoured eight baby sparrows and their mother. Zeus had turned the snake to stone. And Calchas had interpreted the sign: The nine birds were nine years that Troy would withstand the siege, only to fall in the tenth. The tenth year has come at last, Odysseus assures the troops: We are on the verge of success.

|

|

|

|

Nestor now proposes that Agamemnon arrange the troops by tribes, so that he can see which contingents are brave and which are cowardly. Agamemnon agrees and calls up a vast review. But first the men must eat, to steel themselves for the coming battle. A prayer is offered up to Zeus.

|

|

|

|

Agamemnon and his captains enact the ritual that begins a feast. Sacrificial animals are gathered around the altar and their horns are sprinkled with barley. Then their heads are tilted back and their throats are slit. Meat from the thighbones is wrapped in fat and topped with choice bits from the rest of the animal. When this is placed on the fire, the smoke and savor will rise up to the gods as an offering. Then the men skewer bits of the organs to taste while the rest of the meat is spitted over the flames.

|

|

|

|

Hunger satisfied, heralds summon the troops to the review. So vast is the army that the sunlight flashing on their bronze armor is compared to a forest fire. The earth shakes from the tramping of their feet and the horses' hooves. Their vast numbers are like the swarms of flies descending on the shepherds' milking stalls in springtime.

|

|

|

|

And as shepherds divide out their individual flocks, so the troops — no longer thinking of home but eager to fight — are now arranged into contingents by their captains. Menelaus (meh-neh-LAY-us), Agamemnon's brother and the jilted husband of Helen, leads sixty shiploads of men from Sparta and the other cities of Lacydaemon (la-se-DEE-mon). Nestor commands ninety ships from Pylos (PY-los) and its neighboring towns. Eighty ships have come from Crete (kreet) under the command of Idomeneus (eye-DOM-en-yoos).

|

|

|

|

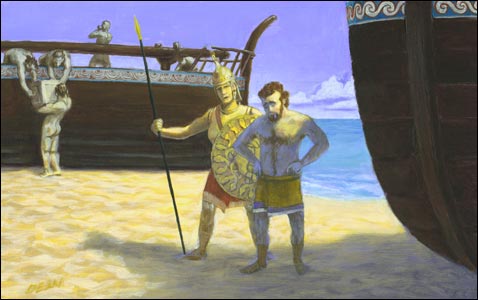

Great Ajax (AY-jax), the best fighter after Achilles (a-KIL-eez), has brought 12 ships from the island of Salamis (SA-la-mis), while the other Ajax, called Little Ajax to distinguish him from his towering namesake, leads the men of forty ships from Locris (LOH-kris). He is the best spearman of the Greeks. Odysseus has brought twelve ships from the island of Ithaca (IH-thuh-kuh) and allied regions of western Greece. Diomedes (dy-uh-MEE-deez) leads eighty crews from the rich surroundings of Argos (AR-gos). And Agamemnon himself has brought 100 ships from his mighty domain centered on Mycenae (my-SEE-nee). In all over 150 cities and towns have sent hundreds of ships to support the Greek cause.

|

|

|

|

Zeus sends for his messenger, Iris, to alert Hector, the leader of the Trojans. Iris takes the form of a sentinal, but Hector knows the voice of a goddess when he hears one. The Trojans are outnumbered by the Greeks better than ten to one, but they have drawn on allies throughout the region. So it is a comparably vast horde that Hector now calls to arms and sends out to counter the Greek host.

|

|

|

|

Note:

|

|

|

|

like the swarms of flies — Homer uses similes — comparisons often introduced by like — to make the violence of war more vivid by comparing it to everyday scenes of its opposite, peace.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|